Text message: I’m so glad I realized I was in the wrong room. I love my teacher. He speaks English and is white. Not being racist. I’m so happy.

I’m not going to say who sent me this except that she’s a freshman at K-State, used to live with me until very recently, and is NOT white. And let’s just call her Helen. She got in the wrong section of business calculus because she went with a friend the first day and stayed there two weeks before figuring out it wasn’t her class. That first teacher was a new graduate student from India. From the imitation Helen did of the young woman asking questions that no one answered (well, to give her some credit, it was 7:30 in the morning), I could tell that she was trying hard to be a good teacher but was up against a triple whammy—a strong accent, lack of teaching experience, and little knowledge of the way American college undergraduates think. And they certainly aren’t very patient with any teacher, let alone one with the accent thing going on.

I asked Helen if she was really glad that her teacher was white and she said it was a joke. I want to believe it was. She seems to take a lighthearted approach to her Chinese American status in a mainly white family (Rose helps move the percentage a little). She loves to tell me that “white chicks don’t tan” and I only wish that my reflective skin was the only thing I didn’t like about my legs. When she got comments from classmates at her rural high school, such as “How do you see when you smile?” she accepted that it wasn’t said in a mean spirited way. I, on the other hand, felt more offended and suggested she use her hands to open up her eyes super wide while saying, “So how do YOU see when you smile?” Quite a clever comeback, right? And so mature.

I grew up in Topeka, home of the historic “Brown vs. the Board of Education” with parents of differing views on non-whites.When a friend of my mother’s called to tell her I had been seen dancing with a black guy at the 9th grade party, she simply replied, “Really? That’s nice.” But when a boy of Asian descent came to the door to collect me on a date one year later, it was my father who rushed to ask my mother if she knew about this. He came by his prejudice rather honestly. His mother, a quarter Cherokee herself, told my brother that he “should stone any nigger that came into his classroom”. My father was horrified at that advice, though not likely as much as my mother. I can clearly remember one morning as I was heading out the door to school. My parents were discussing Rosa Parks. In one of the few times I ever heard her raise her voice, my mother, waving a newspaper in the air, asked, “Why should she have to sit in the back of the bus?” My father didn’t answer but he was surprised to see how much passion she had over this matter.

Always a southern gentleman, my father never acted anything but polite to that boyfriend he had rushed to inform my mother about, and never suggested that I shouldn’t go out with him. But I know he was relieved when the next guy at the door had paler skin. So when I announced that I was going to China to adopt a daughter, he looked stunned but said nothing. In fact, he continued to say nothing, refusing to mention it for the nine months that I waited to get her, something that hurt and angered me. My mother tried to excuse him—he was worried about me having enough money to take on a child and also, remember that he was in WWII when Japan was the enemy—and China, well, it’s also Asian. So I didn’t quite know what to expect when I arrived home with Helen, a child I thought was the most wonderful 20 month old in the whole world, an opinion my mother and brother seemed to immediately agree with.

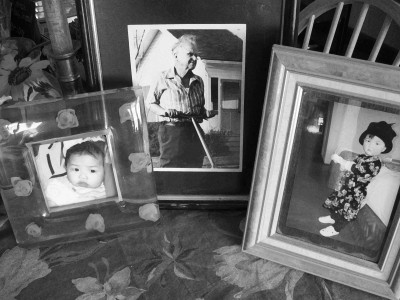

I don’t remember when things changed. It’s been a long time since I showed up at their door with Helen dressed in a red and black checked dress that I still keep in the closet. And it’s been a long time since my father died, two years later. I just remember certain things. Like the way he called her “my sweet little girl”, the same thing he called me at that age. Like the way they would sit together on the front porch, not doing much, just hanging out together. Like my mother’s favorite story about the two of them. It was in the last months of his life, when his feet were so swollen they couldn’t fit in his shoes. We were at their house for Sunday dinner and when he and Helen didn’t show up at the table, my mother went searching, fearing he had fallen. She found him sitting in his chair, smiling down at a little girl who was so gently putting his feet into slippers.

I have to say I feel relieved that Helen can now understand her teacher in a class that will be difficult in the best of circumstances. And I see how it’s what she wants (at some point she also said that he’s rather cute). It certainly is easier to stay with what we’ve known, and what she’s known is mainly white teachers born in this country. But how sad for her if she does what some students do, avoiding classes with teachers whose names don’t sound “American”. I think about what my father would have lost if he hadn’t had Helen as part of his family. At some point in the civil rights movement, he came to agree with my mother about Rosa Parks, but he never spoke out with any of her passion. Later, he was forced to view it much more closely. It was then that this passion showed as he looked down on his “sweet little girl” from China.